Twitter or Mastodon: Centralization and Decentralization

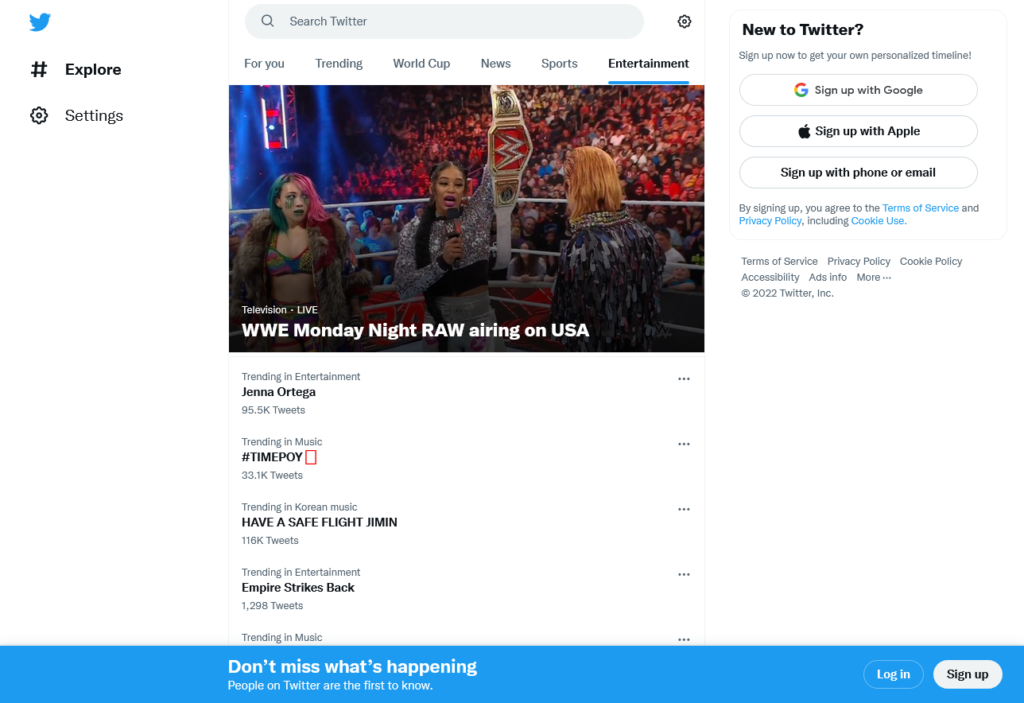

In the blink of an eye, it has been a month since Twitter changed ownership. The chaos that occurred on Twitter during the month was eye-opening and caused many users to lose confidence in the platform and choose to close their accounts and quit Twitter. But social networking is after all an immediate need, so Mastodon, which focuses on “decentralization,” became the destination of a mass migration. Within a week of Twitter’s delivery, Mastodon welcomed 230,000 new users; by early December, the total number of users was approaching eight million.

But as many ‘Twitter refugees’ soon discovered, Mastodon was not the ‘promised land’ they had expected. First of all, the barrier to entry for Mastodon is not low at all. Decentralization means that Mastodon has no “master site”, only “sub-sites” built by the community itself. So, your first step is to choose one of the various “instances” (independent subsites) to sign up; many people are already confused at this step. Next, you have to relearn a set of functional vocabulary. Many people who got on board in a hurry found it completely impossible to understand how to browse and subscribe to posts across sites; some of the features that Twitter users are used to, such as private messaging and global search, had no equivalent in Mastodon. In fact, the recklessness of the influx of new users has recently caused a growing backlash from the ‘natives’, the early users of Mastodon. This is quite similar to the decline in the quality of the community caused by the influx of college freshmen into the then-popular online space Usenet every September in the 1990s, which has led one commentator to call it a contemporary re-enactment of the “never-ending September”.

In addition, Mastodon’s mechanism is fundamentally anti-viral, which is no small culture shock for first-timers. For example, the stream is strictly chronological and there is no push for hot posts; retweeting with comments is not allowed because early adopters resent non-nutritious recommendations. Many people may not realize that although the mainstream platform, represented by Twitter, is often criticized for being full of sensationalistic or off-the-wall information, their habits and expectations have actually been domesticated and they unconsciously start to adapt; once they really come to a “paradise” like Mastodon, they will be overwhelmed like city dwellers left in the countryside.

Mastodon’s decentralized approach to content moderation may also not be able to adapt to the reality of a massive expansion of users. Unlike mainstream platforms that have unified content standards and review rules, and dedicated review teams and response mechanisms, each subsite of Mastodon is highly autonomous and has its own rules, and the core team of Mastodon believes that by relying on the winners and losers among sites and users voting with their feet, it is possible to maintain reasonable rules and appropriate content within the ecosystem. But the facts show that this is also to prevent the gentleman not to prevent the small man. It is foreseeable that if Mastodon goes further into the mainstream, it will inevitably have to face the kinds of difficult content that Twitter is facing today. By then, relying on the ecological self-healing ability and users’ self-awareness to help themselves may not be enough to face the content management problems in a timely and effective manner.

More importantly, like all products that were expected to replace mainstream platforms, Mastodon lacks the core monopoly asset that Twitter has – the social graph. According to the theory of network externalities, the value of a platform-based service to its users is highly correlated with the total number of users. Despite the surge in users, Mastodon’s network size is still a drop in the bucket compared to Twitter, which has hundreds of millions of users. Even while acknowledging that social networking is not about more people, it is important to note that Twitter also serves as a public infrastructure, such as government communications, media coverage, and public scrutiny, which Mastodon cannot do with its current reach.

Of course, this is not to deny Mastodon’s value. Before the influx of Twitter immigrants, Mastodon actually served relatively well as a communication space for small and medium-sized communities with common interests, geography, or backgrounds; and to some Mastodon users, calling it a social network is a misinterpretation that devalues the uniqueness that comes with a decentralized structure. But the current state of affairs does suggest that if Twitter is indeed to be replaced, it may be replaced not by Mastodon as it is, but by a model that is somewhere in between in terms of centrality.

For example, some arguments point out that rather than starting a completely separate platform, a centralized Twitter platform and social graph of relationships should be retained. In this model, users can choose whatever timeline they want to display on their homepage, with the official Twitter original being just one option; other companies can develop and sell ‘alternative timelines’ with different areas of focus or filtering criteria, such as sports-themed timelines, long tweet timelines, timelines for each of work and personal relationships, and so on. This is actually a claim that many people are already simulating today through trumpets, lists and other methods.

If Mastodon illustrates the problems that can arise from migrating a traditionally centralized application to a decentralized system, another recent hotly debated event – the collapse of the cryptocurrency exchange FTX – complements it, offering a reflection on decentralization in a different direction The recent collapse of FTX, another hotly debated cryptocurrency exchange, complements this by reflecting on the inevitable centralization factor in decentralization.

Originally one of the leading exchanges after Binance, and known to the general public for its sponsorship of prominent basketball, baseball and sports teams, FTX went into a rapid collapse starting on November 6. At the time, there were reports that FTT, a cryptocurrency issued by FTX, was held in large quantities by its affiliate Alameda, suggesting possible misappropriation of customer funds and connected transactions. On November 11, FTX, previously valued at $32 billion, filed for bankruptcy. According to reports, FTX lent customer funds to affiliates for investment transactions and had major loopholes in its account management, with the founder even able to tamper with the accounts through a software backdoor, which was described by the bankruptcy liquidator as a “complete failure of corporate governance”.

The FTX event was shocking because it was a disproportionate contrast to the ideal picture that the crypto industry has always portrayed. In that narrative, ‘code is law’ and users’ funds are securely stored in ‘smart contracts’ that are traded automatically and rationally in ways and at prices determined by programs and formulas. All this process is open and auditable, and third parties have no right to interfere, let alone misappropriate it. And the chaos within FTX is possible precisely because it (and most of the current mainstream exchanges) is actually highly centralized, with users’ funds deposited in an escrow account controlled by the operator, and the way they are traded and used ultimately depends on the operator. Thus, commenting on the FTX debacle, JP Morgan equity analysts declared that “all of the recent crashes in the crypto ecosystem have come from centralized players, not from decentralized protocols.” A practitioner also commented in an article in the Wall Street Journal that “it was centralization that caused the FTX fiasco.

But does that mean the problem can be solved by eliminating centralized exchanges and returning to their decentralized roots? I’m afraid it’s not that easy. As many commentaries have pointed out, the cryptocurrency industry is rapidly recreating patterns and inventions that have been seen in the history of traditional finance, while also rapidly repeating accidents and tragedies that have been seen in the history of traditional finance. This is both a result of the basic law of value and human nature, as well as the inevitable result of crypto being used in real-life scenarios and promoted to the general public. Reality shows that only a few people really study and practice crypto and decentralized governance as a theory and an ideal. Most of the remaining participants are not keen, or even completely ignorant, of these abstract issues, but are simply seeking an additional avenue for investment or trading. They do not have the will, nor the ability, to independently participate and contribute to the decentralized system in the absence of guidance and assistance. In other words, centralized exchanges are not anomalies per se, but rather products of the marketplace.

More importantly, no technology can operate in a vacuum. As long as people’s daily lives have not been massively shifted to virtual worlds like the ‘metaverse’, crypto cannot avoid dealing with the physical world and its existing order. Obviously, peer-to-peer communication cannot turn virtual currency into fiat money out of thin air, nor can algorithms and code grow hands to move goods and execute assets. Thus, no matter how much fundamentalists defend the purity of decentralization, those uses that matter most to ordinary people will also force it to introduce elements of centralization – be it exchanges, arbitrators or regulators.

The mishaps of Exodus Twitter and FTX may collectively show that for technology platforms, centralization and decentralization cannot and should not be polar opposites, and that the pure pursuit of either is unsustainable and detrimental to technology and product rollout. The ideal solution is often a mixture of different degrees of centralization and decentralization, requiring both decentralized mechanisms to ensure fairness and transparency, and centralized forces to provide infrastructure and perform public functions; the question is not whether to choose centralization or decentralization, but how to allocate the weight between the two, in what links to adopt them respectively, and through what mechanisms to check and balance the respective shortcomings of the two. It is at this concrete and pragmatic level that the discussion of centralization and decentralization becomes more meaningful.